Several years ago, the year 2000 to be exact, I decided I was going to read all those books that people said they had read when in fact most people hadn't: Darwin, Freud, Marx, the Koran, the Bible, the Russians (Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, then Chekov, Gogol and Grossman), Cervantes, Dickens (all of them), the Americans and so on. I managed mostly and very rewarding it was too, with some exceptions. A book I never got all the way through but I've been chipping away at ever since is the Bible. And recently I began picking at it again. I read the gospels when I was growing up and specifically Mark because our religion teachers told us it was 'the most Catholic gospel', which in itself tells you a lot about how denominations approach the Bible. Now I no longer believe in God, but I'm a Catholic atheist - 'The Fool hath said in his heart, "there is no God"' - and I revisit the Bible again and again with fascination. Sometimes, it's for the novels - Job is a particularly brilliant tale. Sometimes it's for the history/biography. The Jesus stuff always feels like a detective story. We have four witnesses to a crime but their versions are muddled and contradictory. Sometimes they don't even make sense standing alone and they're not consistent with the actual history. As often happens with witnesses, they're out to cover things up and shift the blame (see how Pontius Pilate gets let off and the Jews shoulder the guilt). Lurking through them is the sense that something actually happened, but what exactly is as unavailable to us as the distant future, more so. The future we'll eventually get to, but the past is irretrievable. I'm currently reading the Psalms. Whinging, pleading, threatening, bullying, coaxing, boasting and glorying and doubting. A lot of doubt. They are a cacophony. There's a great one I think 59 all about deliver me from my enemies, 'scatter them by thy power', great stuff. And then Psalm 60 begins 'O God, thou hast cast us off, thou hast scattered us'. Oops. W.H. Auden once spoke of different types of readers, one type would skip the genealogies, the lists of chieftains drawn up in battle order, the litanies and beatitudes because they were basically looking for the story. The other kind, including poets like Auden, would pour over those parts because it was about the language, the poetry, the sound, the effect of those words going through you regardless of whether you understood, like repeating the names of the dead, like a spell. A magic relationship to language. I'll readily admit to skipping my fair share and I still do. I love Thomas Pynchon, but his song-writing skills leave a lot to be desired and when ever he breaks into verse I let out a mild whoop and skip to the end. But increasingly I find myself lingering on the lists and the lines. The way Hunter S. Thompson claimed to have typed out The Great Gatsby, just to feel those words going through you. There's something to that.

1 Comment

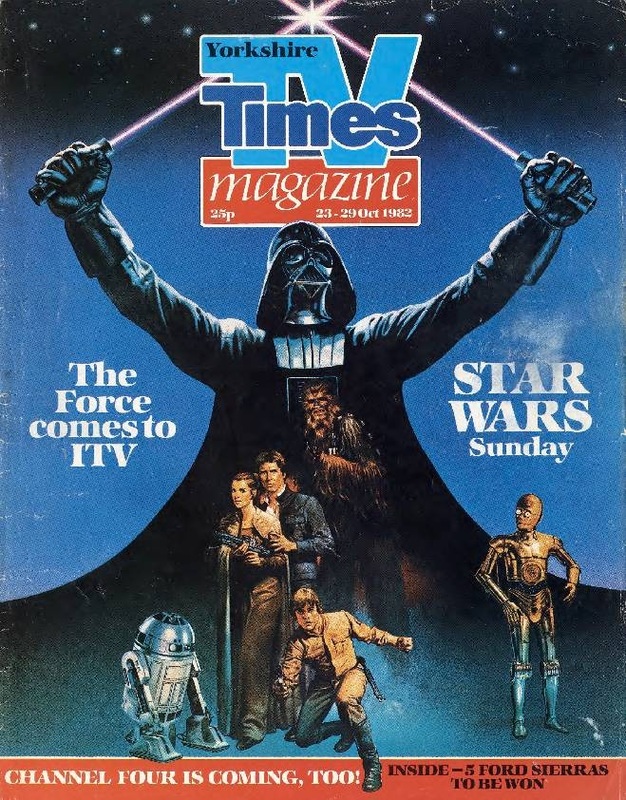

The first film I ever saw at the cinema was Star Wars. I was six years old and we queued outside the cinema in the cold in the North of England and by the time we made it into the packed auditorium the front crawl had already crawled and the Storm Troopers were storming the rebel ship. I would not see the complete film until 24th of October, 1983 when it debuted at 7.15 in the evening on ITV, at the time Britain’s only commercial TV channel. Five and a half years had passed and yet Star Wars had been a constant in our games, our toys, listening to the soundtrack, reading and re-reading George Lucas’ first novel with ‘16 pages of color illustrations’.

Today the situation is obviously different with instant downloads, simultaneous DVD release, or at the longest a wait of a few months before a film can be owned and re-watched over and over again, complete with audio commentary, deleted scenes, and perhaps an alternative ending. And though I don’t want to wax whimsical about the good old days, I do want to emphasize, state, the amount of air that could exist around a film. In this space, there was plenty of room for rumor and speculation and the legendary director’s cut, the first 6 hour version of a film was a commonly repeated theme, the cut would be butchered and hacked back by an unsympathetic Studio and what we saw was a remnant of the artist’s vision. An example of this was a film that had been planned as a follow up to Star Wars, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and was released in the UK a full year before, in the Fall of 1982. The rumors of a five hour version were encouraged by the film’s narrative ambiguity, some apparent inconsistencies (how many replicants?) and later by the occasional surfacing of late night TV showings which include bits no one remembered. The rumors were also encouraged once more by the space such thinking had to play in. The lack of internet sites – from encyclopaedic collections such as IMDB to the plethora of geek out blogs – meant that such speculation took place in the letters pages of fan magazines and on the bus to school, with very little ground for confirmation or decisive rebuttal. It also helped that Blade Runner evoked a world which seemed to stretch far outside the frame of the cinema screen or the VHS pan and scan TV screen, the first way I got to see Blade Runner. The idea of an epic five hour film was sustained by the idea that Los Angeles in 2019 looked such a big and detailed world. There was room to explore. Such hopes and illusions came crashing down with the release of Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut in 1992. Although it gave us the opportunity of seeing this film – most of us for the first time – on the big screen, it decidedly was not the five hour epic of the director’s vision. In fact, it was shorter than the original release. The changes were at once momentous and weirdly inconsequential. The theories about Deckard being a replicant – encouraged by a close reading of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – were rendered explicit; out went the off-cut from The Shining in went the off-cut from Legend and banished was the sleepy nourish narration (which I guiltily still love: ‘no one advertises for a killer in a newspaper’). With the further release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut complete with a five disc edition containing deleted scenes, all the major alternative versions and a documentary about the alternative version, the legend was now the province of purists, pedants and the bird spotters of cinema, a frame here and rerecorded line there. Clarity was given not only in the remastering of the image but by eliminating those beguiling inconsistencies (how many replicants?) and, more damagingly, ambiguities: ‘I want more life, FATHER.’ Nowadays, the director’s cut is no longer a mysterious legend but a marketing tool, a way of boosting ancillary sales and a counter in getting director’s to compromise on the theatrical release. Watching a Ridley Scott film at the cinema seems almost a waste of time, as we do so knowing full well that his director’s cut will be on the way with an introduction by Scott at the beginning, grumpily disavowing any compromises made. Robin Hood, Black Hawk Down, American Gangster and most dramatically Kingdom of Heaven all had big director’s cut releases often with a cynical delay to allow the dedicated the joy of effectively buying the same movie twice. The latter is often cited as a director’s cut which vastly improves on the original, but I would argue 1. the increased amount of Orlando Bloom offsets any subplot and 2. given it is a better version why didn’t Scott fight for it tooth and nail. I can only watch a film for the first time once, so that experience should be optimal. Director’s cuts encourage carelessness and compromise even as they pretend to authenticity and definitiveness, sometimes providing opportunities for endless noodling with flawed material. See Oliver Stone’s Alexander, Alexander: The Director’s Cut and Alexander Revisited: The Final Cut, or better still, don’t. Then there are the restored classics. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Time in America was famously butchered by the editor of Police Academy at the behest of the studios. Even though there has been a longer European cut available for some time, a new version was recently released in Italy which restored many missing scenes, but what the film gains in coherence it loses as a watching experience. The film stock has obviously degraded and there is a glaring difference in footage quality with the lost scenes. For a restored version of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, the original cast now in their sixties and seventies overdubbed additional scenes to a similarly jarringly effect. A restored scene in Spartacus between Tony Curtis and Laurence Olivier had Anthony Hopkins doing an impersonation of Olivier in the overdub. The dream is always that hidden treasure will be found, a lost version restored, the director’s vision finally realised, but time and again films are significantly damaged by these interpolations. Of course these aren’t necessarily director’s cuts. They are alternate versions and, as with the recent rerelease of The Shining, there is evidence to suggest the directors’ might well not have wanted their films released in these version. Sometimes less is more. Director’s cuts exist also in the context of ‘Unrated Versions’ of comedies (more tits, less funny), and horror movies (more gore, less scary). Having given you everything so quickly and so completely, there is still the need to shove the idea that you are somehow getting more, quantity though and not necessarily quality. ‘Including 23 minutes of previously unseen footage’ doesn’t promise much except perhaps the studio wanted an R, and the director gave them an NP-17. As a film writer, I can’t bemoan the availability of all these versions (although that is kind of what I’m doing). However, I can register disappointment. Disappointment that the universe is shrinking. Now we can see the director’s second thoughts and they are rarely as good as their first. Films become flabby with additional scenes and that sense of unseen possibility is stymied and ultimately destroyed. The experience I had between 1977 and 1982 of nurturing the memory of a film and reliving it in so many ways can’t ever be regained, but with all our wealth of cinematic accessibility it is worth remembering some of the positives that came in the austere time, when Han Solo shot first and Jabba wasn’t CGI.  I spend so much of my time glued to a screen in one way or another. Either a computer, a smart phone, a large screen television or inside the womb dark cinema. I should get out more. And I try. And I love it when I do. My perfect day would be spent walking in the mountains in the morning, maybe go for a swim in the afternoon, or sit and read a book in the garden and then a trip to the cinema in the evening. That would be great. A few years ago I made a concerted effort to do more walking. I live in a place surrounded by some of the most beautiful mountains in Europe, the Dolomites are about an hour away in the car, Monte Grappa is even closer. But if I turn left when I leave my house, from the gate at the bottom of the garden, I can walk up out of the village and up a mountain which is almost 1000 meters (3280 ft) high. Ben Nevis is only 300 meters higher and a far longer drive. I regularly walk part way up the mountain, and more occasionally get to the summit, although as often happens with mountains, there turn out to be there are actually several summits. That's what makes mountain walking amazing, the way it changes your perspective very literally. Suddenly the village becomes a map of the village, the course of the river is visible, other mountains appear behind the mountains as you achieve an altitude that allows you to peak. The mountain that you're climbing often disassembles as you explore it. Bits you thought were part of it turn out to be quite separate. The sound changes as well. The noise of the village, the busy main road and the industrial zone follows you as you climb the mountain for the first hour, but once you get past a certain ridge, the noise vanishes and you are away. As you near the top, the sun burns brighter, the wind is stronger, the air is fresher. On a good day you can see Venice. It's moments like these, away from the pallid fun of screens, the Asperger's like obsession with film trivia and cross references, up there above it all that I can finally escape my own head. I stand on the summit at one with nature and think to myself: 'This is just like the end of Last of the Mohicans (Michael Mann, 1992).' In fact, I've been having these thoughts all the way up. The bit with the long grass (Thin Red Line), the path that goes through the trees (Fellowship of the Ring, I always say 'Get orf the road!' as a tribute), the craggy bit (The Deer Hunter). I can't see nature except through movies. I can't see anything without thinking of books and film. It is pointless even trying. It's self-deluding, stupidly self-denying. This is what I am. If I ever became one with nature (and got rid of all that other stuff) it simply wouldn't be me. As Captain Kirk says in Star Trek V, 'I need my pain'. |

AuthorJohn Bleasdale is a writer. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Independent, Il Manifesto, as well as CineVue.Com and theStudioExec.com. He has also written a number of plays, screenplays and novels. Archives

March 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed