|

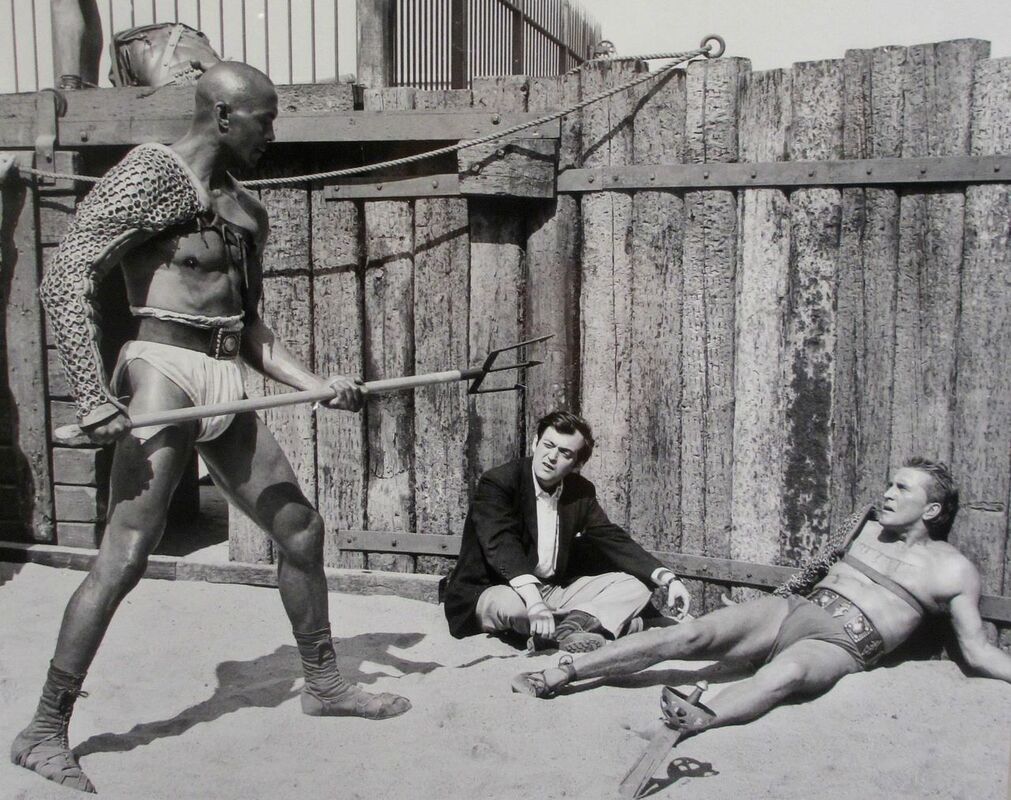

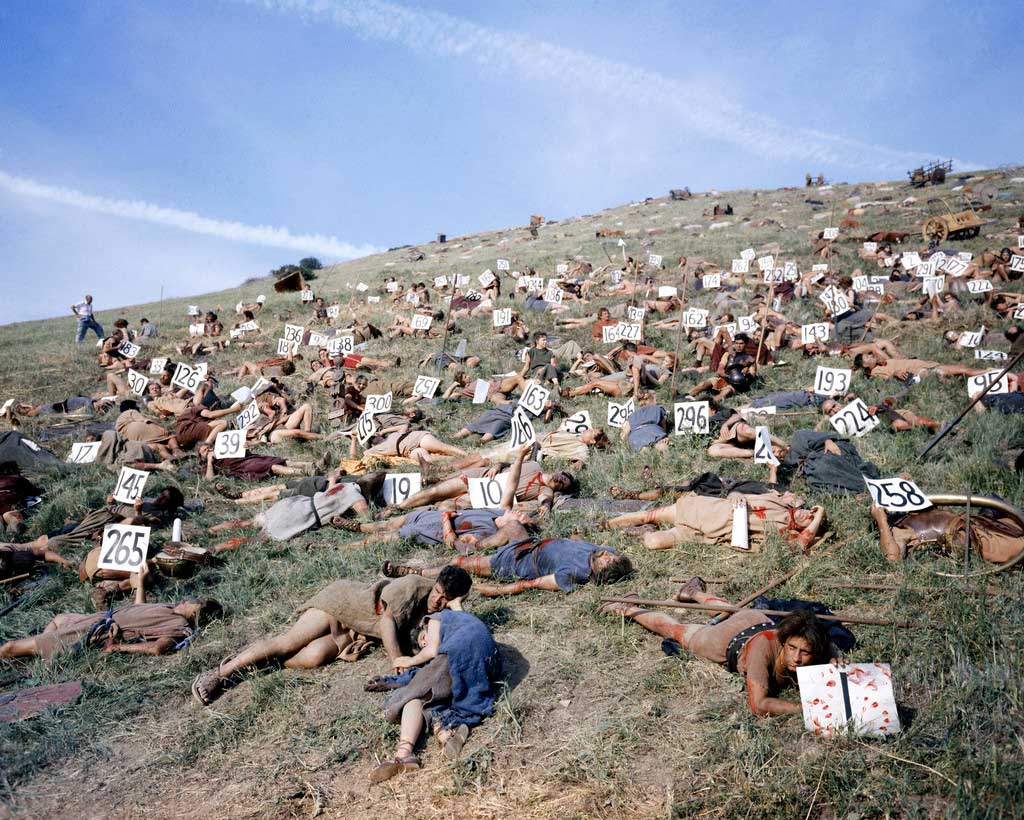

The difficulty of Spartacus is that for Kubrick it was definitely a promotion but at the same time also a demotion. The budget was bigger, the cast as well and this was by far the most ambitious film he had ever attempted - perhaps would ever attempt in terms of logistics - it literally had a cast of thousands. But at the same time, he was a hired director. He hadn't developed the work - it was the baby of the film's star Kirk Douglas - and some of the footage in the finished film wasn't even his. Director Anthony Mann had been feared early on and Kubrick brought in to replace him. So how was this really a Stanley Kubrick film at all? The story of Spartacus properly begins with Kirk Douglas' disappointment at losing out to Charlton Heston for Ben-Hur, a role he had campaigned for. There were also the Hollywood studios who wanted to prove that you could make a sword and sandal epic in Hollywood. Except for the large scale battle at the end - filmed in Spain using Fascist troops - most of locations were in California. The story is simplicity itself. As Russell Crowe might have it the Thracian who becomes a slave, the slave who becomes a gladiator, the gladiator who becomes a revolutionary. Slave trader Batiais (Peter Ustinov) buys Spartacus (Douglas) and has him trained in his gladiator school in Capua. Here he falls in love with Varinia (Jean Simmons in her most plummy accent), a love that has no room for expression and is taught to fight. In one of these combats to please visiting Crassus (Lawrence Olivier), a fellow slave (Woody Strode) refuses to kill him and is killed as a result. A rebellion soon breaks out and Spartacus leads a gladiator army seeking to escape the wrath of Rome and befriending singer of songs Antoninus (Tony Curtis), along the way. Spartacus has a lot of weight to bear on its epic shoulders. Two massive talents in Kirk Douglas and Stanley Kubrick, who obviously grabs his opportunity with both hands. It also has the legendary breaking of the black list, with Dalton Trumbo being allowed to keep his name on the script despite being declared a communist. The film itself has definite political overtones. The disgust at the Patrician class covers not only Olivier's Crassus but also to some extent Charles Laughton's populist, whose dishonesty is more humane but whose need to keep the slaves down is just as fervid. The film is beautifully photographed and Kubrick's framing and pacing is throughout exceptionally confident. It manages to achieve scope and scale without ever feeling overblown and there is an attention to detail that humanises everything. The slave army is portrayed through a series of montages that also include old people and children, grounding the world and taking the aspic out. Despite being the hired hand, Kubrick doesn't seem to have held back. He criticised the screenplay wanting Spartacus to demonstrate some flaws and he basically told the cinematographer that his job was to sit in a chair with his mouth shut while Kubrick acting as his own DP. Claims that he wanted have the writing credit for himself would be consistent with his manoeuvres to water down Jim Thompson's credit in the past but it should also be understood that in Douglas' memoir he wanted to diminish Kubrick as a way of promoting his own contribution. And that contribution is visible. The film has a keen wit - particularly with the Romans: Olivier, Ustinov and Laughton. In fact, the slaves become faces following the rebellion. The love affair between Spartacus and Varinia is pretty spunkless, though she does get pregnant. The triumphs are the set pieces - of which there are three truly great ones. The fight to the death in the gladiator school is brilliantly choreographed and realised and the image of the dead Woody Strode hanging from the ceiling is a political resonant coda. The final battle between the slave army and the Romans is superb in its scale and set up and clear in what is happening. Some of the gruesome parts just look silly now. This isn't The Wild Bunch, so a sword through the neck or a lopped off arm seem out of place. But the burning logs and the way Kubrick picks out Douglas as he rides through the mayhem is impressive. The latter also seems to reference a similar set up from Paths of Glory. The final set piece is the aftermath of the battle and the crucifixions. I'm not sure if set piece is the right descriptor here but this is so recognisable as to be immediately open to parody and Life of Brian did so to the extent that it is difficult to watch Spartacus without immediately thinking '...and so is my wife.' Spartacus hasn't got the bloat of Ben-Hur or Cleopatra. It is handsomely filmed and well acted. The music by Alex North is fantastic, especially the love theme and the music that precedes the battle. But for Kubrick the lesson he learned - according to his biographers and later interviews - was that he never wanted to be a director for hire again. In reality, that revelation probably came later after his Billy the Kid movie with Marlon Brando led to a torturous development, followed by his firing. If anything Spartacus looks like a young director who is able very competently to tick the boxes, including keeping his big name stars happy. His decision to disown it later feels like a repudiation of the genre rather than the film itself. Certainly, this is Hollywood product from beginning to end - even the painterly composition - but Kubrick's hand is still visible and there's something to be said for being able to work within the strictures of Hollywood and create something that is so creditable. It also allows Kubrick to feel that he has sounded the full range of his register. He can do the intimate black and white noir or the 70 mm technicolor epic. So what does he want to do next? Get as far away from Hollywood as he can. And then Lolita of course.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Bleasdale is a writer. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Independent, Il Manifesto, as well as CineVue.Com and theStudioExec.com. He has also written a number of plays, screenplays and novels. Archives

March 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed