|

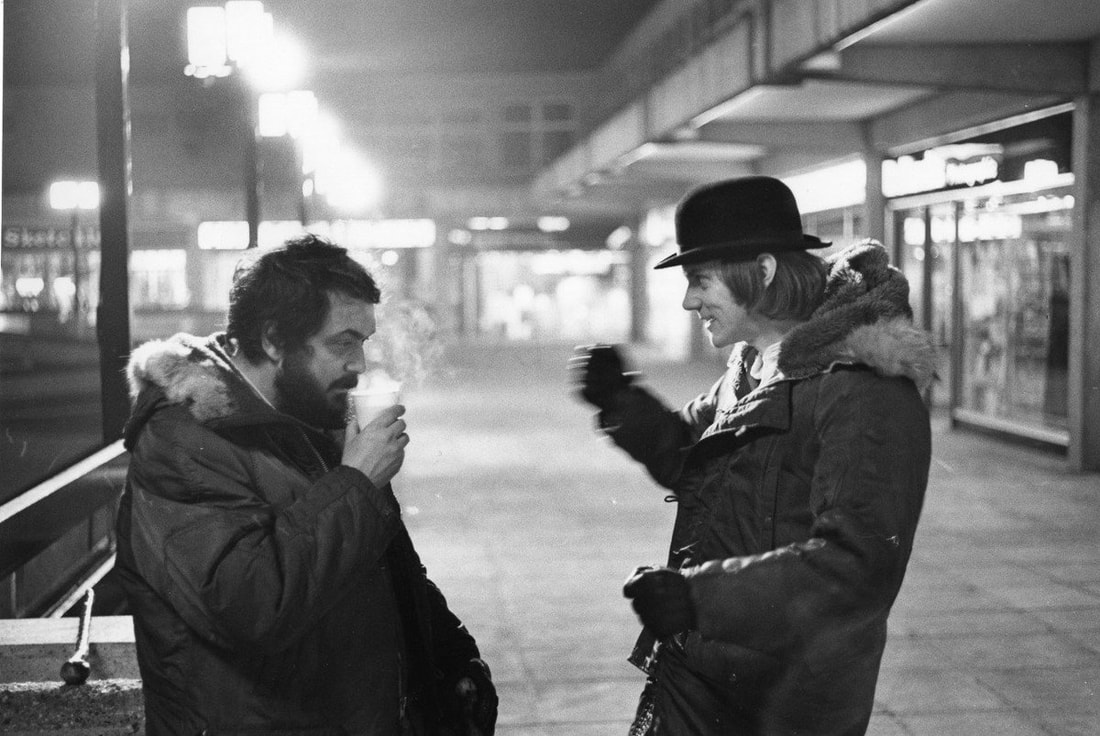

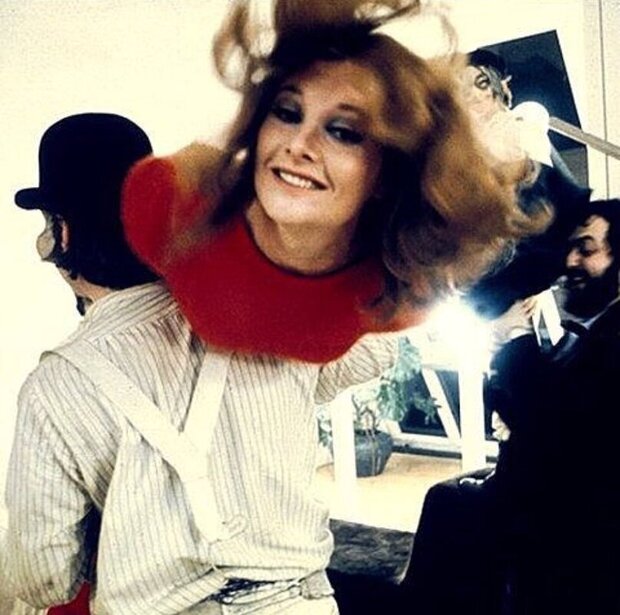

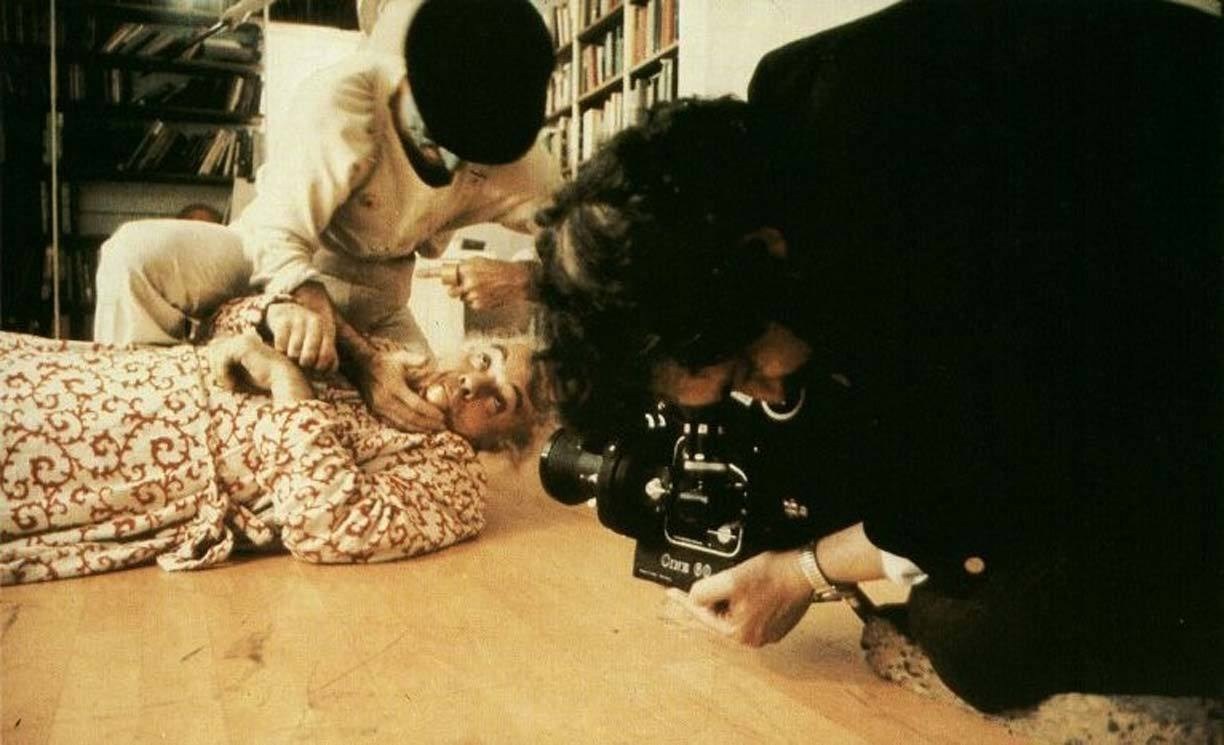

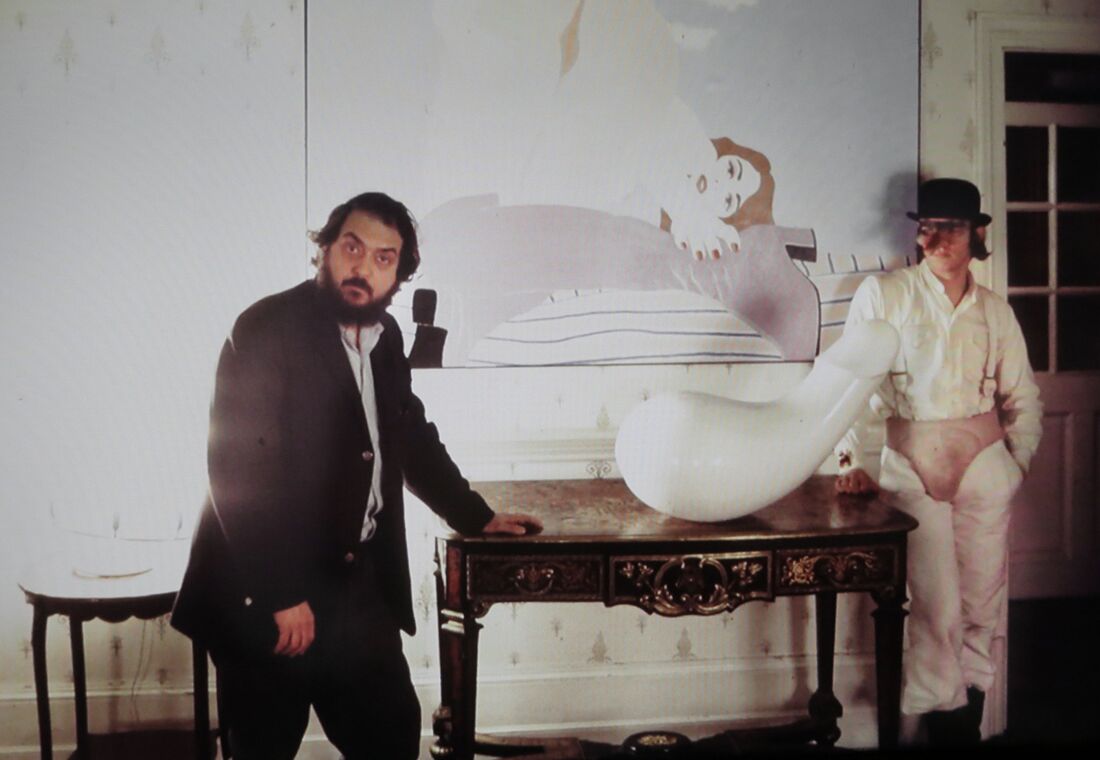

A Clockwork Orange is what happens when a master filmmaker decides to deliberately make an ugly film. Following the ecstatic star journey of 2001, we come down to Earth with a thudding bump which is traumatic, at times hilarious and something utterly different. Based on the novel by Anthony Burgess, the story is of Alex de Large, Malcolm McDowell in a performance that at once made and destroyed his career. Alex and his three Droogs prowl the night looking for ultraviolence and rape, culminating in the home invasion of a writer and his wife. His career is curtailed when his erstwhile friends betray him and he is sent to prison for murder. Following some years of confinement, Alex is unreformed, reading the Bible only so he could enjoy the sex and violence he finds therein. However, he is picked for a new experimental form of aversion therapy which will force him to feel nausea when contemplating violent or anti-social acts. Unfortunately for Alex, part of the therapy involves the music of Beethoven, a composer he loves, and so he is deprived of this pleasure. Released into the world a 'free' man once more, Alex comes across all his former victims, each of whom enact the revenge on the now defenceless young man. Writing out the synopsis, two things become apparent to me. First of all how much this film has the narrative simplicity of a children's story. The people we meet on the way up are then the people we meet on the way down. There's a pleasing and obviously non-realistic symmetry which also presupposes a moral. This is a moral tale, at least structurally. So what is the second thing. Well, that goes to the moral. What is the moral? Of course, when it was released Kubrick, but mainly Burgess, defended the movie as a deeply moral examination of the price of freedom. That freedom was put in the abstract and absolute, but it's actually a very specific freedom: the freedom of young men to do what they want. The idea that we are to weigh in the balance Alex's love of Beethoven with his love of rape is remarkably dated. Of Kubrick's movies, this is the film which has dated the most - it is more dated than Spartacus and certainly more dated than 2001, even though 2001 even has its date in the title. Male freedom to rape is put against the freedom to listen to music and at no point against the freedom of women, you know, to not be raped. Women have almost no voice or perspective in the film except as weeping Devotchkas, some health care professionals and the screaming harridan of the cat lady who has her mouth shut by a giant dick. Without any sense of the suffering of the women involved - and in fact one potential rape and the cat lady's murder are played for laughs, the film is definitely rapey.  Kubrick certainly chooses Clockwork Orange as a radical change from his previous film. Going back to my initial remark about how much of the film is ugly, it is worth reiterating. This master of framing and composition makes a film of almost unbearable ugliness. The furniture, the hair, the art within the film, the locations, the decor, the light: the soundtrack is a combination of distorted electronic music, jokey classical placements - the William Tell Overture over an orgy - and occasional pomposity, Beethoven and Elgar. The camerawork involves shaky handheld, sudden zooms, unconvincing back projections, the light flares and bleeds in the lense. And what happens in the film is fairly grimy as well, from the drunken tramp to Mr Deltoid spitting in Alex's face. And the tone of the film is garish in its extremes: a broad exaggerated comedy - 'Show some reverence you bastards' - which targets all the authority figures ranked against Alex. One of the reasons Alex is so compelling is that he provides some aesthetic control with his white overalls and bowler hat, often occupying the center of the frame and commanding the slow motion and the tracking shots. But none of this is necessarily to be taken as a criticism of the film. I don't think Kubrick effed it up. In fact, this is decidedly consciously ugly garish uncomfortable work. it is an assault on the kind of good taste that 2001 certainly represented. Look at the violence. Although the film garnered a reputation as a violent film, even being withdrawn from UK distribution by Kubrick following a media backlash, the film has no real aesthetics of violence. There's a slapstick quality perhaps but the battle between rival gangs is played like a western shot by the Keystone Kops. There's no Peckinpah sense of gruesome beauty, nor is there anything really harrowing about the assault and rape of Adrienne Corri. Despite his admiration for Kubrick, Gaspar Noé's explicit gruelling shock cinema is a million miles away from this. This is a film with a nihilistic take on the whole of society. There is no one who is respectable as an authority figure or sympathetic as a victim. Liberals are deluded; conservatives are corrupt: all art is pornography with the exception of classical music, but even then... when Alex's listens to Beethoven his face is that of a man coming in his pants. A Clockwork Orange is the beginning of punk. A deliberate rejection of good taste and deliberate satisfaction for the exhilarating amoral thrill of anarchy. There are other earlier films - see for instance Toshio Matsumoto's Funeral Parade of Roses which Kubrick cited as an influence - but A Clockwork Orange launched it into the mainstream. Its lasting impact today is on fashion and creating an iconography via Alex and his Droogs. All of that occurs in the first half hour of the movie and much of what occurs in the rest of the film gets forgotten. I first saw the movie on a video cassette of exceptionally poor quality with Dutch subtitles. It was difficult to tell how much the soundtrack was supposed to be distorted. And yet even today when I watch it that first grubby viewing, now in pristine remastered blu-ray quality retains its ability to shock, appal and make me laugh. The spittle dripping from Alex's face is now crystal clear.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Bleasdale is a writer. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Independent, Il Manifesto, as well as CineVue.Com and theStudioExec.com. He has also written a number of plays, screenplays and novels. Archives

March 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed